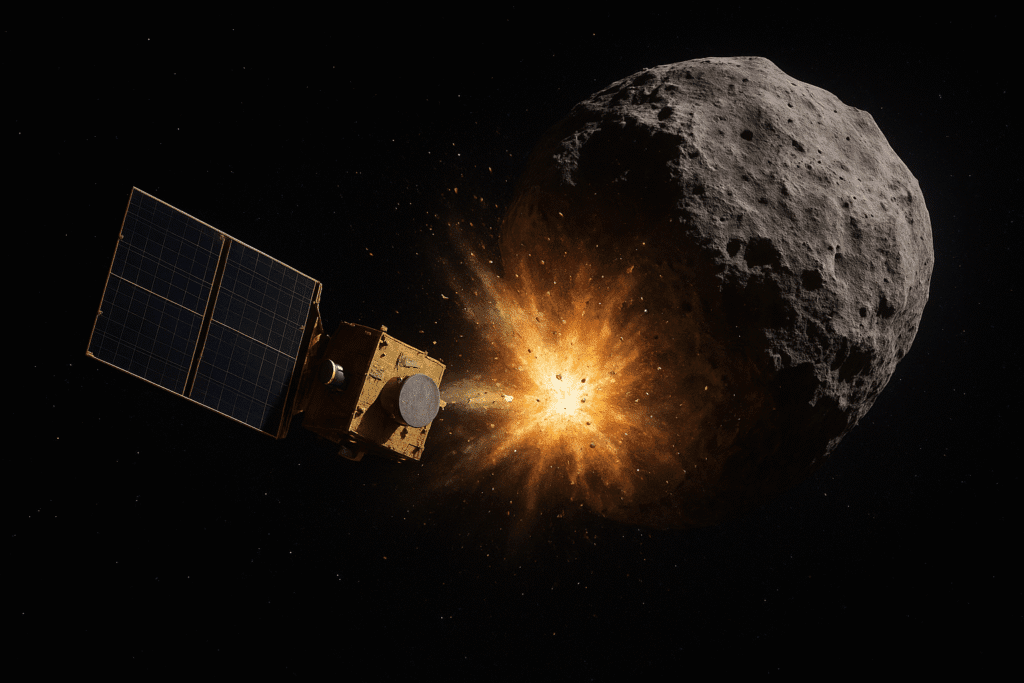

In September 2022, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission by NASA made history: for the first time, humanity attempted an asteroid deflection test by intentionally crashing a spacecraft into it. Its target: Dimorphos, the small moonlet of the binary‐asteroid system orbiting Didymos. The main goal was simple yet profound: to test whether we can alter an asteroid’s path and so one day defend Earth from a genuine threat.

The Mission of Asteroid Deflection Test: A Clear Success

When the DART spacecraft collided with Dimorphos, scientists expected a modest shift in its orbit, on the order of minutes. But the results were far beyond baseline expectations. Pre-impact, Dimorphos completed its orbit around Didymos every 11 hours and 55 minutes. After the impact, the orbital period shortened by about 33 minutes.

Essentially, a relatively small spacecraft (about the size of a vending machine) proved that a kinetic impactor can significantly alter an asteroid’s trajectory, a major step for planetary defence.

The Puzzle: Unexpected Behaviours and Hidden Complexities of Asteroid Deflection Test

While the mission’s headline result (orbit shortened) was a clear success, deeper analysis revealed puzzling outcomes that complicate our understanding of asteroid deflection. Here’s what stands out:

- Momentum beyond the impact: Researchers found that the momentum transferred to Dimorphos exceeded what the spacecraft itself delivered. This was due to large amounts of ejecta, rocky debris blasted off the surface, which acted like a secondary “rocket-blast”.

- Strange debris behaviour: A new study found that many of the boulders ejected from the asteroid did not spread uniformly. Instead, they formed clusters with distinct trajectories, some moving almost perpendicular to the asteroid’s original orbit. This was unexpected and suggests that the surface structure and internal makeup of the asteroid play a major role in how deflection works.

- Possible shape and orbit changes: Post‐impact analyses showed that Dimorphos may have changed shape (from a “squashed sphere” to more elongated) and that its orbit may have become slightly eccentric rather than a perfect circle.

- Lingering uncertainties: Some changes were detected weeks after the impact and are still not fully explained. For instance, a further slight shortening of the orbit (seconds rather than minutes) might have happened, but whether this represents real physical change or measurement noise remains open.

Why This Matters for Future Asteroid Deflection Missions

These puzzles are important because future missions aiming to protect Earth from hazardous asteroids will require precise predictions of how an asteroid will respond to a deflection attempt. Miss a variable, and you might change the orbit in unintended ways, or worse, fragment the target into unpredictable debris.

- The fact that ejecta momentum dominated means simply hitting the target isn’t enough: the internal structure and surface composition (loose “rubble pile” vs. solid rock) will significantly alter outcomes.

- The directionality of debris matters: if rocks fly off sideways or in unexpected directions, the net effect on the asteroid’s orbit could be different from what is predicted.

- Shape change and orbit evolution: Altering an asteroid’s spin, shape, or mutual gravitational interactions (in the case of binary asteroids) adds complexity.

- Risk of unintended consequences: Some studies even raise scenarios where fragments or ejecta might pose secondary risks (though not in this DART case).

Asteroid Deflection – What We Learn Going Forward

The DART mission demonstrates two things: 1) that asteroid deflection via kinetic impact is viable; and 2) that our models need refining. With these lessons in hand, scientists are planning follow-up missions, such as the Hera mission by the European Space Agency (ESA) to study the Didymos/Dimorphos system in even greater detail.

For planetary defence strategies, the takeaway is clear: detection alone isn’t enough. We must understand the target thoroughly, its composition, structure, rotational state, binary nature, and model the asteroid deflection accordingly with contingency plans for unusual behaviour.

Conclusion

The DART mission was a landmark for human space exploration and planetary defence. But the “puzzling outcome” isn’t a failure, it’s a reminder that the universe doesn’t always behave in simple, textbook ways. Each mission teaches us more about the unpredictable nature of space rocks, and each lesson refines our ability to protect our planet.

As we look ahead, the success of DART gives hope, and the mysteries it revealed give purpose. The next time a dangerous asteroid heads our way, we’ll be better equipped not only because we can hit it, but because we’ll better understand how it will respond when we do.

Explore more fascinating space topics in our Space Buddy section.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What was NASA’s asteroid deflection test?

NASA’s asteroid deflection test was the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission, which intentionally crashed a spacecraft into the asteroid moonlet Dimorphos in September 2022 to see if its orbit could be changed.

Did the DART mission successfully change the asteroid’s orbit?

Yes. The DART mission successfully shortened Dimorphos’s orbital period around its parent asteroid Didymos by about 33 minutes, far exceeding initial expectations and proving asteroid deflection is possible.

Why was the outcome of the DART mission considered puzzling?

Scientists observed unexpected effects, including extra momentum from debris ejecta, unusual debris movement patterns, possible changes in the asteroid’s shape and orbit, and lingering changes detected weeks after the impact.

What role did ejecta play in the asteroid deflection?

The impact blasted large amounts of rocky debris off Dimorphos. This ejecta acted like a secondary thrust, increasing the total momentum transferred and making the deflection more effective than the spacecraft alone.

Why did the debris from Dimorphos behave unexpectedly?

Instead of spreading evenly, many debris fragments clustered and moved in unexpected directions. This suggests Dimorphos has a complex surface structure, possibly a loose “rubble-pile” composition.

Did the DART impact change the shape of the asteroid?

Post-impact observations indicate that Dimorphos may have changed from a slightly flattened shape to a more elongated form, which could affect how it moves and rotates in space.

What does this mission teach us about future asteroid deflection efforts?

The mission shows that while kinetic impact works, accurate deflection requires detailed knowledge of an asteroid’s structure, composition, spin, and whether it is part of a binary system.

Could asteroid deflection create dangerous debris?

In theory, poorly understood deflection attempts could produce risky debris. However, in the DART mission, no debris posed a threat to Earth, and all outcomes were safely observed.

How does this mission help protect Earth?

DART proved that humanity has a working method to alter an asteroid’s path, a crucial step toward planetary defence against potentially hazardous near-Earth objects.

What mission will study the DART impact further?

The European Space Agency’s Hera mission will arrive at the Didymos–Dimorphos system to closely examine the crater, debris, shape changes, and orbital dynamics caused by the DART impact.

Is asteroid deflection guaranteed to work in every case?

No. Each asteroid is different. The DART mission showed that one-size-fits-all models don’t work, and future missions must be tailored to each target’s physical characteristics.

Why is the DART mission still considered a success despite the mysteries?

Because it proved asteroid deflection is possible and highlighted the complexities scientists must account for, making future planetary defence strategies smarter and safer.